The idea of ‘Green’ in Asia is dominated by certification tools. There are now some 14 national variants – not unlike LEED in the US – each offering tiered ratings at the building scale, some at the urban scale. The rating is determined by an aggregated score, the result of compliance with requirements that focus on measurable outcomes such as energy and water efficiency.

Biophilic design has a more qualitative goal, specifically human well-being tied to the presence of natural elements in buildings, such as greenery and water, or access to attributes and qualities found in nature. This can be hard to measure but is often highly visible since it affects architectural form and appearance.

It should be said that Green too recognises the importance of well-being but the focus here is on physiological well-being through the principle of avoidance. The design team is told, in effect, what not to do¹ in the interest of occupant health and comfort. Biophilic design targets psychological well-being on the grounds that everyone has an innate affinity for nature. The approach here is salutogenic affordance: what to do to improve well-being.

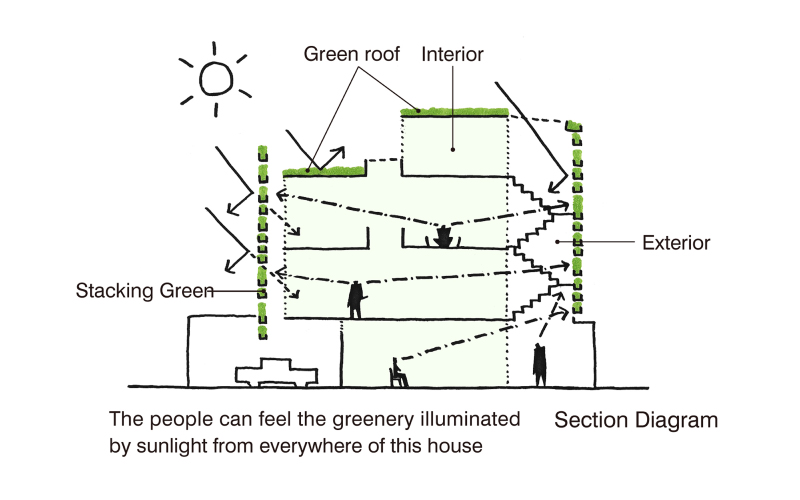

Stacking Green, Drawing by Vo Trong Nghia

What do building users think matters more?

Some 2000 occupants of 11 office buildings in Singapore – a mix of Green certified and non-certified developments – were surveyed on their perception and expectation². Asked if they thought they were in a Green building, a sizeable number in non-certified buildings , almost 14%, said ‘yes’, suggesting a baseline expectation of Green that is not linked to certification.

Asked what they thought was a Green building, the group as a whole – including those in certified buildings – mentioned plants (21.5% of responses) and daylight (19.6%). Energy and water efficiency, sensors, controls and recycling – the focus of many certification tools – were in the subsequent four spots. Certification itself, as a marker of what is a Green building, was mentioned by only 2.4%, a low figure given that almost a third of all buildings in Singapore are presently certified³.

When the same group was asked to pick features/attributes that reduce stress, six of the top ten turned out to be biophilic: presence of plants (58.5%), views out (57%), access to daylight (44.2%), water features (43.9%), courtyard spaces (35.2%) and sounds of nature (35.2%). Only three correspond with certification requirements: noise control (65.4%), air quality (61.3%) and temperature controls (51.2%).

Stacking Green by Vo Trong Nghia, Image by Hiroyuki Oki

User response is unequivocally biophilic. What about certification tools?

Fourteen Asian Green certification tools were reviewed4. All tools seem to say greenery and water are important but almost none link these to the question occupant well-being. Of the two, greenery is sometimes parked under ‘Ecology’ where it is tied to natural systems (for instance, the need to preserve existing habitats within project site). Enhancement of green cover is mentioned by some but this is often linked with goals like ‘reduced urban heat island effect.’ The potential of water – salutogenic or ecological – is ignored. The tools are interested in conserving water, and little else.

The review then looked at biophilic attributes: access to daylight and natural ventilation, view to outdoors. The most valued of these are daylight (9 out of 14 tools ask for this) and natural ventilation (8 out of 14). The clauses here often carry a caveat on comfort, worded as the avoidance of visual or thermal discomfort. Tellingly, the clause itself can be parked under ‘Energy’, not ‘Indoor Environmental Quality’. The least valued is view to outdoors; 10 out of 14 tools do not mention this or ask for it in only for some building types.

Stacking Green by Vo Trong Nghia, Image by Hiroyuki Oki

The most biophilic tool in Asia is Lotus (Vietnam) in which some 18% of achievable credits are linked to natural systems or biophilic features5. The least biophilic tools, accounting for about 5% or less of possible score, are GRIHA (India), LEED India (India), TREES (Thailand) and GreenSL (Sri Lanka)6.

On the whole, it appears, Asian tools are not deeply biophilic. Biophilic principles are undervalued, either missing or (mis)placed in a category other than well-being. And because these tools drive the definition of Green, it follows that the Green building in Asia does not actively seek biophilic design as a pathway to well-being.

This said, there are notable exceptions.

Biophilic Design in Asia

Green Mark version 5 (non-residential), currently in pilot stage, has changed the vocabulary of certification. In a clause on greenery, the team is called on to “integrate a verdant landscape and waterscape that is accessible for all to enjoy… to enhance the biodiversity around the development and provide visual relief to building occupants and neighbours.” In another clause on ‘Well-Being’, biophilic design is explicitly discussed as provision of “elements of nature… to nurture the human-nature relationship… for the health and happiness of the building users.” Version 5, compared with the current version, almost doubles the emphasis on natural systems and biophilic features, accounting for over 20% of possible score, making Green Mark the most biophilic tool in Asia. It will be interesting to see how version 5 changes the look and feel of future Green buildings in Singapore. Other tools, like GRIHA, in newer versions, are also increasing the weightage placed on this although they still lag behind in the final tally.

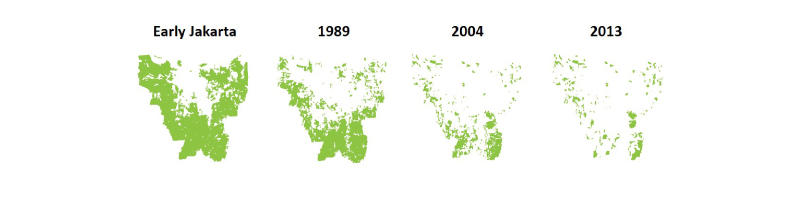

Depletion of urban green cover in Jakarta, Indonesia. Drawing by class of MSc ISD progamme, National University of Singapore, based on Nasa Earth Observatory

Exceptions aside, the general lack of interest in biophilic design is a missed opportunity in Asia because well-being – in many cities – is compromised for the majority of residents. Many cities have been systematically stripped of blue-green cover; once accessible green spaces and waterways are replaced by grey infrastructure and gated communities.

Case in point: the city of Jakarta (Indonesia), since its early days as a metropolis, has seen a loss of green space – from 24% to 9.9% of city area – with a parallel loss of its water footprint from 4% to 2.5%. Green space available to the poor is now estimated at 0.19 m2/person; the affluent have 6.537. In the same period, urban density rose from 10,075 to 13,157 people/ km2, with peak density now close to 50,0008.

Degradation of waterways due to industrial pollution and dumping in Jakarta, Indonesia; Image by Giovanni Cossu

In a recent study9 it was reported that this transformation has impacted the quality of life in Jakarta. Jakarta was once a water city. Rooted in culture and religion, water was positively perceived. Developments in recent decades have altered this, creating new anxieties and phobias for water. Factories, buildings and roads have turned rivers in narrow concrete, polluted canals; access to rivers and green spaces has been curtailed. This, in turn, has triggered a change in habits; a new generation of Jakartans pollute rivers with garbage and sewage. Waterways have lost their social value, becoming an open dump.

In cities like Jakarta there are no real alternatives to better policy and planning. But until that happens, buildings can do much to compensate. Biophilic design ought to be the centrepiece of design guidelines in Indonesia. Greenship, Indonesia’s Green certification tool, however, offers 7% of available credits to this.

Degradation of waterways due to industrial pollution and dumping in Jakarta, Indonesia; Image by Giovanni Cossu

With tools, there is another problem. Elements and strategies that affect well-being are often parked under something other than well-being. This mis-framing matters. Greenery to reduce urban heat island is good but it carries no obligation for occupant access or enjoyment. As a result, many green roofs are unseen or unreachable.

The Singapore survey of office buildings suggests that Green, at least in the mind of users, is biophilic. It stands to reason that making Green tools adopt biophilic design principles could increase public interest in certified projects. Developers complain that they’d like to go Green but there is too little consumer buy-in. Well, there is now a way to change that.

This review of Asian certification tools was carried out in collaboration with Shuchi Jhalani, a post-graduate student at the School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore.

Additional Reading

1 These are typically parked under ‘Indoor Environmental Quality’ in which outer limits of acceptability are stipulated (for instance, the upper and lower limits of indoor air temperature). The project is penalized if it exceeds these limits.

2 The 2012 study was carried out by Kishnani, N. (National University of Singapore), Tan, B.K. (National University of Singapore), Bozovic Stamenovic, R. (University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia); Prasad, D. (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) and Faizal, F. (National University of Singapore). It was sponsored by Singapore’s Ministry of National Development through its research fund for the built environment. It was carried out in collaboration with the Building and Construction Authority (Singapore).

3 Building Construction Authority, Singapore (2015); Realising Singapore’s Green Building Dream – Towards a Future-Ready Built Environment. Singapore

4Asian Green certification tools

1. Green Mark (Singapore): RB version 4.1 + NRB version 4.1

2. GBI (Malaysia): RNC version 1.02 + NRNC version 1.02

3. Greenship (Indonesia): All buildings, version 1.1

4. BERDE (Philippines): VRD version 1.1.0 (2013) + CB version 1.1.0 (2013)

5. Lotus (Vietnam): R version 2.0 + NR version 2.0

6. BEAM Plus (Hong Kong): All buildings, version 1.1 (2010.04)

7. CGBL(China): Residential version 2006 + Commercial, version 2006

8. EEWH (Taiwan): EEWH-RS version 2007 + EEWH-BS version 2007

9. TREES (Thailand): All buildings, version 1.1

10. CASBEE (Japan): All buildings, 2011 Edition

11. KGBC (South Korea): Multi-unit residential version 2002 + Others version 2002

12. GREENSL (Sri Lanka): All buildings, December 2010

13. GRIHA (India): SVA GRIHA, version 2013 + All buildings, version 3

14. LEED (India): All buildings, version 2011

5The review looked at clauses for achievable credits only. Most tools also have pre-requisites clauses for which no credits are awarded.

6To put this in perspective, the WELL Building Standard – a new certification tool dedicated solely to occupant well-being – assigns 33% of achievable credits to natural systems and biophilic features.

7 “Beban Berat Jakarta” on 20 December 2013

9 N. Kishnani and G. Cossu (2015), Enhancing Blue-Green and Social Performance in Dense Urban Environments: Biophilic Design, Singapore’s Khoo Teck Puat Hospital and Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park. National University of Singapore. Sponsored by the Ramboll Foundation

4 responses to “Are Green Buildings Biophilic? Why the Answer Matters, Particularly in Asia”

Good article. Very interesting use of the terms ‘avoidance’ and ‘affordance’.

To date, for the most part, ‘green’ has not considered human or ecological well being, but simply fuel energy usage and sourcing.

In biophilic design, the building’s “Human Energy Effect” is my phrase for describing our focus.

Afterall, even if one goes for “net-zero” in terms of fuel energy, if the building has an adverse impact on human energy, health and well being, what’s the point?! 🙂

By the way, from a Feng Shui Perspective, those curved-top chairs in the lower photo serve a very positively powerful purpose. The curves soften and add “Natural Flow” to the otherwise linear aspects of the beautiful, natural materials of the wall paneling and flooring, and the dominant right-angles of the other structural elements.

The use of Feng Shui Design Principles is a dynamic component of enhanced Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ).

Hi Alisa,

Thanks very much for your comment, and for your mention of the ‘Human Energy Effect’. Please do send us some more information with regards to your theories on this?

Thnkiing like that shows an expert at work

I am glad the human angle is being considered important to the ‘Green’ debate. While green has ended up being a bit like building bye laws, it is necessary to look at it from users perspective and I am glad the biophilia and addition of plant life is seen as an important aspect besides the natural sunlight. The long term impact of the so called green building material is another area that needs to be looked into closely and the rating agencies must monitor their performance over an extended period to understand their efficacy ( or failure).