An Interview with Michael Pawlyn, Architect & Author

In The Biomimetic Office Building, lighting takes its inspiration from the translucent four-eyed spookfish and a spindly-legged cousin of the starfish, the brittle star, both deep ocean dwellers. The building’s glazed glass exterior nods to a mollusk’s iridescent shell, while our own double duty spinal column is echoed in support columns that also encase the building’s energy systems.

To Biomimetic Office Building designer, architect Michael Pawlyn, the natural world teems with models of brilliant design efficiency. Pawlyn’s book, Biomimicry in Architecture, inspired and challenged architects, urban designers and product designers to look to Nature for beautiful models of resource efficiency.

It also called for them to move beyond sustainability, which Pawlyn characterised as “minimising the negatives,” primarily of resource and energy consumption, versus the regenerative model that is biomimicry. The Biomimetic Office Building is the latest project undertaken by Pawlyn and his Exploration Architecture team. The design, which uses biomimicry to rethink the workplace into a self-heated, self-cooled, self-ventilated, day-lit structure that is also a net producer of energy, will strengthen the case for biomimicry by drawing a brighter line between restorative, responsible design and cost savings. In addition to biomimicry, the project incorporates the principles of psychologist, Craig Knight, such as plants in the workplace, to address employee well-being, job satisfaction and productivity.

“The design debate has shifted over the last 10 to 15 years from resource and energy saving to improved productivity,” said Pawlyn. While upon completion the Biomimetic Office Building promises to be one of the world’s lowest energy office buildings, energy costs are tiny compared to employee costs, such as salaries. And according to Pawlyn, design of The Biomimetic Office will maximise substantial human resource investments through gains in productivity of as much as 25 percent.

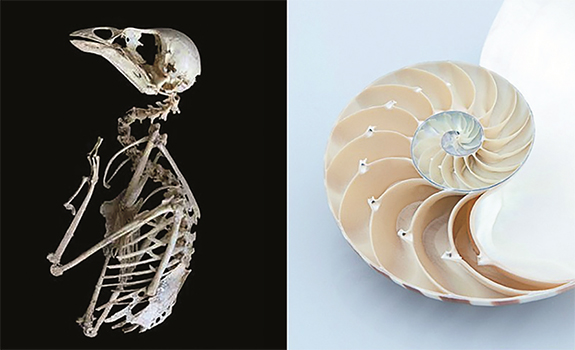

This grounded, practical cost-benefit equation, however, belies the project’s ingeniously fantastic soul. The building infrastructure, for example, is modelled on the bone structure of birds and cuttlefish. Everything about a bird must be light, strong and efficient to enable flight. While delicate, bird bones are actually far from fragile. In particular, their skulls are made from multiple layers of very thin bone. The layers lend strength without the added weight that could impede flight. Similarly, the layers that comprise cuttlefish bones vary to add reinforcement only where the animal needs it for movement, support or protection.

In bird skulls and cuttlefish bones, Pawlyn found that “complex forms that use minimal materials in exactly the right place,” is often the operating principle in Nature, and their ingenuity was incorporated into key structural components of the Biomimetic Office Building, the floor slabs and columns. Sections of the floor that will be “working hard” by taking on more of the stress of the structure and weight will need denser concentrations of concrete. Columns and floor slabs earmarked for lighter duty can be hollow, their voids used for secondary purposes, such as, housing wiring or temperature control components.

The building infrastructure is modeled on the bone structure of birds and cuttlefish. The glazed glass exterior nods to a mollusk’s iridescent shell.

For further temperature control, the building design calls for intricate, identical shades, able to respond automatically and, if necessary, separately to changes in light the way plants such as the mimosa pudica, or sensitive plant, and Venus flytrap move in response to touch or other external stimulation. Another tropical plant variety, the epiphytic anthurium, which grows on other plants close to the rain forest floor and efficiently captures and makes use of scarce sunlight, is providing food for thought for a subsequent phase of the Biometric Office Building design.

In consultation with work space designers and psychologists, biologists and even primatologists, Pawlyn and Exploration Architecture continue to seek innovative design solutions that draw upon the billions of years of wisdom found in Nature, challenging not just our thinking about the final product or outcome, but the very process by which we arrive there.

“Don’t start with reality, start by identifying the ideal and then compromise as little as necessary to meet constraints of budget and buildability,” says Pawlyn. “If you don’t start by identifying the ideal then you’re very unlikely to find breakthrough ideas.”