Even when craftspeople are working to a pattern, handspun or woven textiles are one-of-a-kind items — small variations make each one unique. Saori weaving, created by Misao Jo in 1968, celebrates this idea of random beauty. Unlike other handweaving techniques, Saori is completely freestyle with no rules, restrictions, or samples to follow, and where a deviation is never considered wrong.

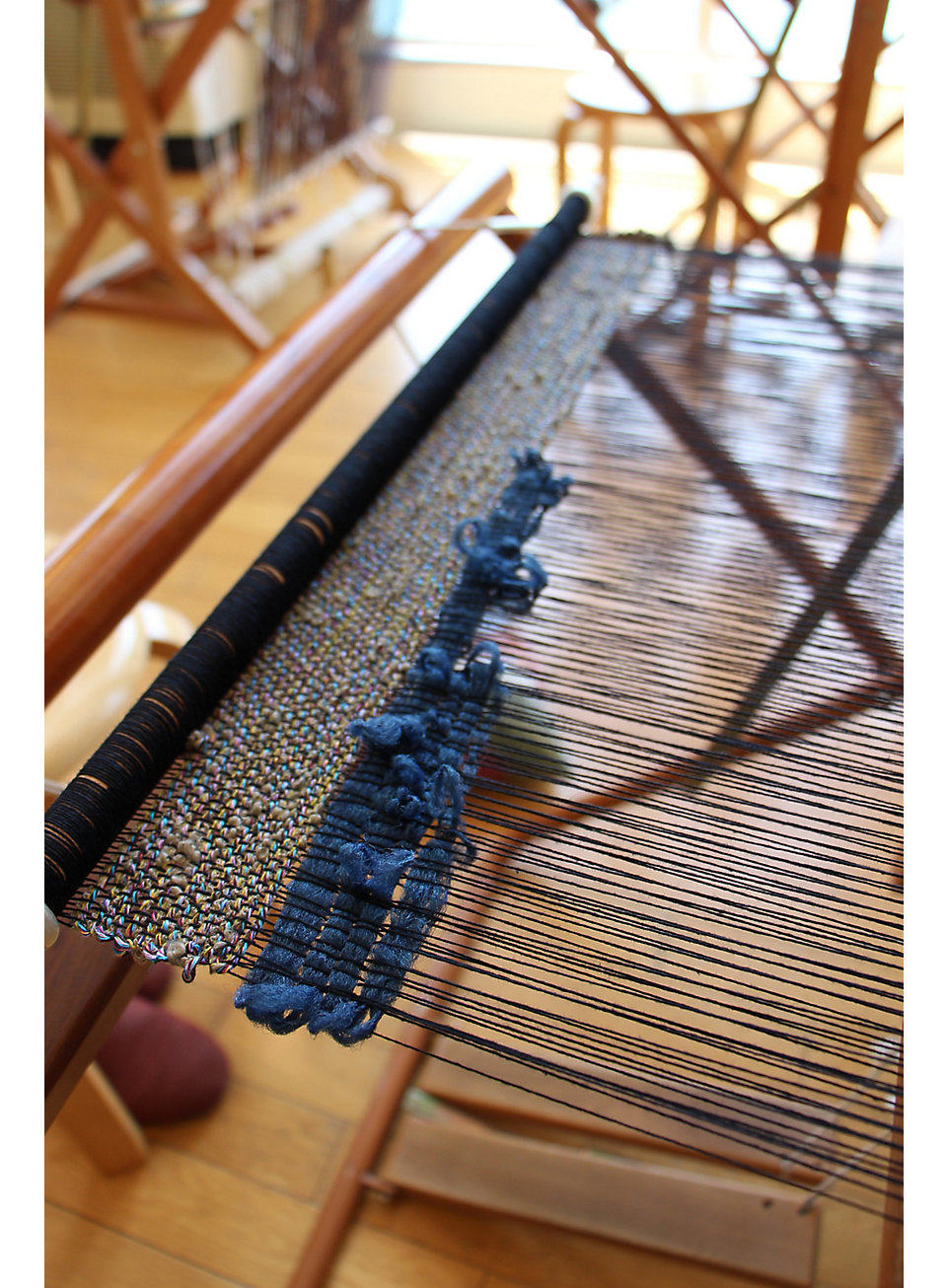

To get a taste of this philosophy, Interface Asia Design Director, Daniel Blois and two Interface colleagues found themselves in a leafy, secluded enclave near Osaka, Japan, home to Saorinomori weaving studio, the birthplace of Saori. Attending an intensive all-day course to understand the process and techniques behind Saori, Blois was in for a surprise: “It was basically a brief lesson in how to use the loom. They walk you over to this big yarn wall, and within 10 seconds you need to select three yarns and just get onto the machine without hesitation.”

Learning to let go

In a society that prizes perfection, intentionally skipping a thread and weaving together a variety of mismatched yarns takes real effort. However, this desire for perfection can be balanced with the Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi: the acceptance of flaws, transience and impermanence. Both are acceptable and seen as noble elements of artistic endeavour. As Blois wove, he found that, “It’s actually a miniature journey of discovery, to just let go, in terms of what I had known and how I formally approached design with my background in interior design. I struggled to let go but eventually accepted whatever occurred along the way.”

There is now a revival of all things nostalgic, natural or handmade – could this be our subconscious rebelling against the unattainable goals of uniformity and perfection? One of Saori’s four pillars is to “Consider the differences between machines and people”, where machine-made implies striving for perfection.

For Blois, this is a challenge to freedom in creativity: “We often embrace the impureness of handwoven rugs. In many cases the rougher, small flaws add more value because it is a weave that is unique and different. Yet, when we start to create things on a machine, you have to be able to replicate it, and there cannot be total randomness. Otherwise, you can’t use or sell it. This potentially leads to process waste as ‘imperfect’ product is discarded, which has been a dilemma for us as we are bound by our commitment towards sustainability.”

Applying Saori philosophy to carpet

Experiencing the art of Saori firsthand was an eye-opener for Blois, as he now wants to build machines that can be programmed to weave at random, integrating freedom and entropy into the mechanical process. During his stay, Blois had the privilege of sitting down with Misao’s son, Kenzo Jo, who engineered the Saori weaving loom and shares the random art form’s connection with nature. Mr. Jo explained that “Japanese conventions are always connected to nature, sounds, the moon and the wind. So to express ourselves, we fall into nature, and that’s very natural for us Japanese.”

This ties back to Interface’s biophilic products. As Blois says, “Not everyone wants leaves, flowers and tree trunks in their office, but there are varying degrees of biophilic design, whether that be putting in a jungle, or subtly capturing the essence of it as in the World Woven Collection. I feel that the Japanese have always had their finger on that as a culture. If you look at how they perceive and represent nature, both literally and pared back – where a single wisp of something can represent a forest. It is so refined in its simplicity. Just like the Haiku, where there’s no excess in words or lines, we can achieve that with design.”

Saori’s spirit of self-innovation could, according to Blois, be expressed by Interface and its design customers in the potential to weave unconstrained floor designs.

“The base component of each Interface product is the individual tile module, while for Saori weaving, it’s each yarn or thread. Perhaps this is another opportunity to revisit our products from a different conceptual perspective. By “weaving” combinations of our modular carpet patterns, textures and colours on the floor, we have further freedom to create something truly unique and random within the interior space, thus echoing the spirit of Saori.”

This level of self-expression and discovery is something that Blois is keen to introduce to the Interface team: “It is said that ‘In Saori, we do not weave only a cloth. We weave our true self.’ The first thirty centimetres of the scarf I wove took me well over a couple of hours and was actually a bit stressful, but once I respected the process – that error is not part of the vocabulary, but part of the beauty – then things just flowed without my realizing a whole day had passed. I have not been much of a spiritual person, but if I have ever experienced anything remotely inwardly enlightening, this was it.”