Singapore’s Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) might well be the most biophilic hospital in Asia. In no other healthcare institution of this scale are elements of form, space and landscape so explicitly tied to the goal of human well-being—the very definition of biophilic design.

The KTPH competition brief, from the onset, asked that the new hospital ought to be a ‘healing environment’, an idea that drew from early research in environmental psychology, linked to biophilia, and which was prescient of trends in Southeast Asian design where architects like Vo Trong Nghia (Vietnam) and Woha (Singapore) experiment with deep integration of plants and architecture.

That brief set in motion a biophilic quest that expanded into five principles:

- Sight, visual access to greenery and water;

- Smell, selection of scented plants;

- Sound of falling water;

- Diversity of plants, birds and butterflies;

- Community, public space situated within blue-green areas.

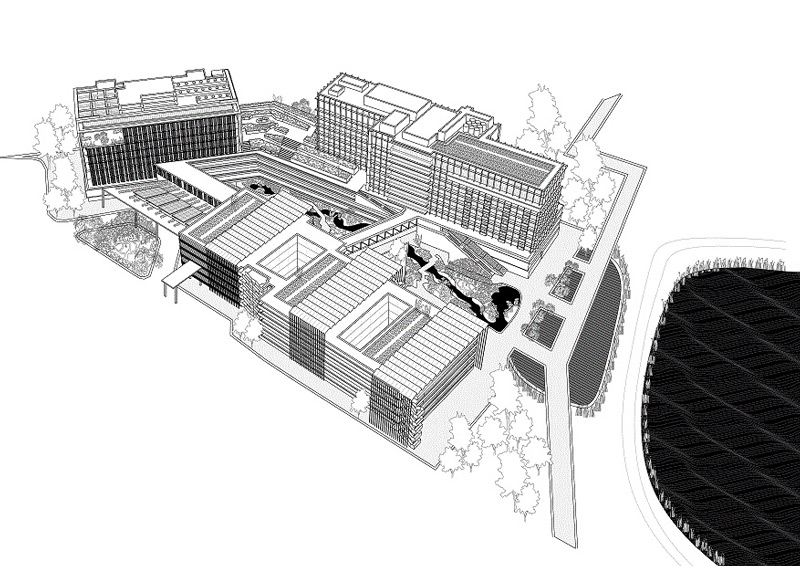

The first concept sketch by winning team, CPG Consultants, showed a V-shaped configuration of blocks, delineating a central court. The ‘V’ opened to the north, letting in breezes that first skim over an existing storm-water pond adjacent to the hospital site. To tap into this natural airflow, the envelope of the buildings had to calibrate permeability and shade. The goal here was that patients could access natural light, cooling breezes, and views without risk of solar glare or rain entry.

The winning concept sketch of Khoo Teck Puat Hospital by CPG Consultants.

The heart of the development, which makes these principles work, is the green court. Designed to be ‘forest-like’, it includes water features with aquatic species and plants that attract birds and butterflies. The greenery cascades to upper levels of the buildings and down into an open-to-sky basement, creating the impression of architecture that is deeply enmeshed in a garden. At the upper levels, balconies with scented plants bring the experience to the patient’s bedside, literally.

The green plot ratio of KTPH – an indicator of how much greenery there is in a development – is 3.92; in other words, the total surface area of horizontal and vertical greenery combined is almost four times the size of the land that the hospital sits on. This is remarkable for a development in a dense urban setting. As a proportion of total floor area, blue-green spaces account for 18%. Forty percent of all such spaces are publicly accessible. In post-occupancy measurements, the microclimate of this court was some 2oC cooler than spaces just outside the hospital.

In 2005, mid-way through design, the KTPH team expanded the hospital’s blue-green footprint by ‘adopting’ the adjacent storm water pond. Collaborating with other government agencies, the hospital team worked out a cost-sharing arrangement whereby the pond – turned into a park – would serve multiple groups from the hospital and neighbourhood. The concrete edges of the pond were hacked away, and new aquatic plants were introduced to clean the water and create habitats. A walking trail was added, linking the park to the hospital and a nearby residential estate. The pond, following the revamp, increased blue-green space available to KTPH patients and visitors by 400%.

Since its opening in 2010, engagement of the community-at-large has been a priority. Residents living nearby enjoy the hospital’s public spaces alongside patients and staff. The KTPH team encourages this, citing its role as public health educator. This has led to the activation of these spaces with community programmes such as line dancing, tai chi and Zumba. Volunteers – mostly retirees – tend to rooftop gardens alongside KTPH staff. Produce from this farm finds its way to the hospital kitchens; some is sold to cover costs.

About 200 users were surveyed in 2016 by researchers from the National University of Singapore. The sample group – randomly selected patients, staff, visitors – were asked how they felt. Another 75 people at an older hospital in another part of Singapore were asked the same questions about their experience. That reference hospital, completed in 1984, represented an earlier approach to healthcare design in Singapore.

On most counts – perceived beauty, self-reported well-being, awareness of nature – KTPH did better than the reference case. Interestingly, assessment of beauty in both projects was found to be linked to six constructs, four of which corresponded with biophilic design, specifically the presence of water and greenery. User well-being (sense of calm, levels of stress) was found to be significantly better in KTPH. Awareness of and perceived closeness to nature was higher in the KTPH group.

Asked if hospitals ought to invest in blue-green elements, over 80% in both hospitals said yes. Asked if they were prepared to pay for this, the percentage saying yes in the older hospital was substantially higher than in KTPH, possibly because there was little blue-green in the former.

KTPH is overwhelmingly liked by staff and visitors. It consistently out-performs all other hospitals in Singapore in the annual Ministry of Health public satisfaction survey. Results of the 2016 study suggest that this preference, at least in part, is linked to the quality of its space and biophilic attributes.

This research was supported by Ramboll Foundation (Ramboll Group A/S) as part of wider research into Enhancing Blue-Green and Social Performance in Dense Urban Environments. A full report can be viewed on http://www.ramboll.com/megatrend/liveable-cities-lab. The study was made possible with the support of Alexandra Health, the owner and operator of Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, and the project team at CPG Consultants.