This two-part article is a collaboration between Bill Witherspoon, founder, Skye Witherspoon, CEO, and myself in my role as Director of Research Initiatives at The Sky Factory. It was inspired by Bill Browning’s Real vs. Simulated Nature section in The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace report, and its timely review to how past studies have sought to simulate a window with a view to nature.

What Multisensory Illusions Reveal about Perceived Open Space

In a fascinating study using Magnetoencephalography (MEG) imaging, Dr. Steve Rose, British neuroscientist and author of The Future of the Brain, observed that visual cortex signal strength is context dependent. That is, the cortex uses contextual cues to actively participate in turning sensory input into perception.

The study he cites involved having subjects identify the shortest bottle from a line-up of several shapes while measuring visual cortex signals. While displaying the same line-up of bottles, the subjects were then asked to choose the bottle they preferred to drink from.

Despite the lack of change in visual stimuli, the wave of activity crossing a variety of cortical regions in the subjects increased, indicating that contextual, as well as structural expectations, play a role in how we process sensory stimuli. After all, it’s one thing to identify a trait (comparative shape) in which we have no stake and quite another to evaluate bottles that will impact our experience (how much liquid they hold or how ergonomic they are to grip or drink from).

If context can be shown to alter our perceived sensory input under simple situations, what would context contribute to environmental design simulations like the one the U. of Washington set up?

What is the difference between the impact of representational imagery when we see it in a painting, a photograph, or as televised content, and similarly derived visual content that gives rise to optical illusions, which alter our experience of the surrounding environment?

Contextual expectations impact how we respond to and interpret sensory stimuli.

Understanding Spatial Reference Frames

In her book, Making Space, How the Brain Knows Where Things Are, Dr. Jennifer Groh, director of the Neural Basis of Perception Laboratory at Duke University, discusses how our memory catalogs spatial reference frames to map out and recognize the environments we move through.

Spatial reference frames are spatial relationships that we have experienced and which we store in our brain as memory. Dr. Groh explains that our brain uses perception of space as a kind of filing system to store and access memories. Therefore, when we gaze out into a clear blue sky with a shimmering water feature and a fluttering canopy of trees nearby, the visual memory is also spatial, which is another way of saying multisensory, not symbolic.

This is one reason why televised content is limited to being representational images. A televised image lacks context.

However, when we encounter a similar visual perspective, say we’re looking out into a successfully simulated view to nature, our memory recognizes the spatial reference frame. The evoked experience makes the multisensory stimuli acquire a borrowed vividness that triggers a genuine sense of expanded space. An illusion of place.

St. David’s Foundation incorporates an illusion of sky to create a simulated atrium. © 2016 Sky Factory

The cognitive misreading occurs due to the interplay of the visual and spatial cues that mimic the spatial reference frame of the stored experience. This comingling lends the misleading cues the veracity of the original memory. Despite our logical understanding of the elements at play, our senses still give rise to a palpable illusion of depth.

This demonstrates an important quality of illusions. Now, how can this knowledge be incorporated to design better nature simulations and measure their therapeutic effect?

Let’s go back to the University of Washington’s study mentioned in Part I of this article.

While the research team at the University of Washington took care to position the flat-screen monitor in a vertical orientation to simulate the same orientation that the window afforded observers, the study did not give the monitor a proper architectural context; that of a real window. Therefore, the proper spatial reference frame that would imbue the high definition visual content with the spatial depth of a real view was lost.

In comparing real views to nature, environmental design researchers might put themselves in the architect’s shoes and think in spatial terms. At the same time, in devising a sound methodology, investigators might opt to study illusionists, allowing experimental variables to account for how our organs of perception operate.

The methodology must understand that creating architectural portals in enclosed interiors is not a matter of visual content alone, but also how multisensory cues weave the tapestry of cognitive perception. Only then, will simulated nature scenarios gain a more realistic measure of success.

These attempts have begun.

The Science of Illusions of Nature

In healthcare environments, where the lion’s share of the research into simulated nature features first started, the differences in clinical outcomes between the benefits of representational nature art and the deeper spatial relief that illusions of nature can provide, is finally gaining academic traction.

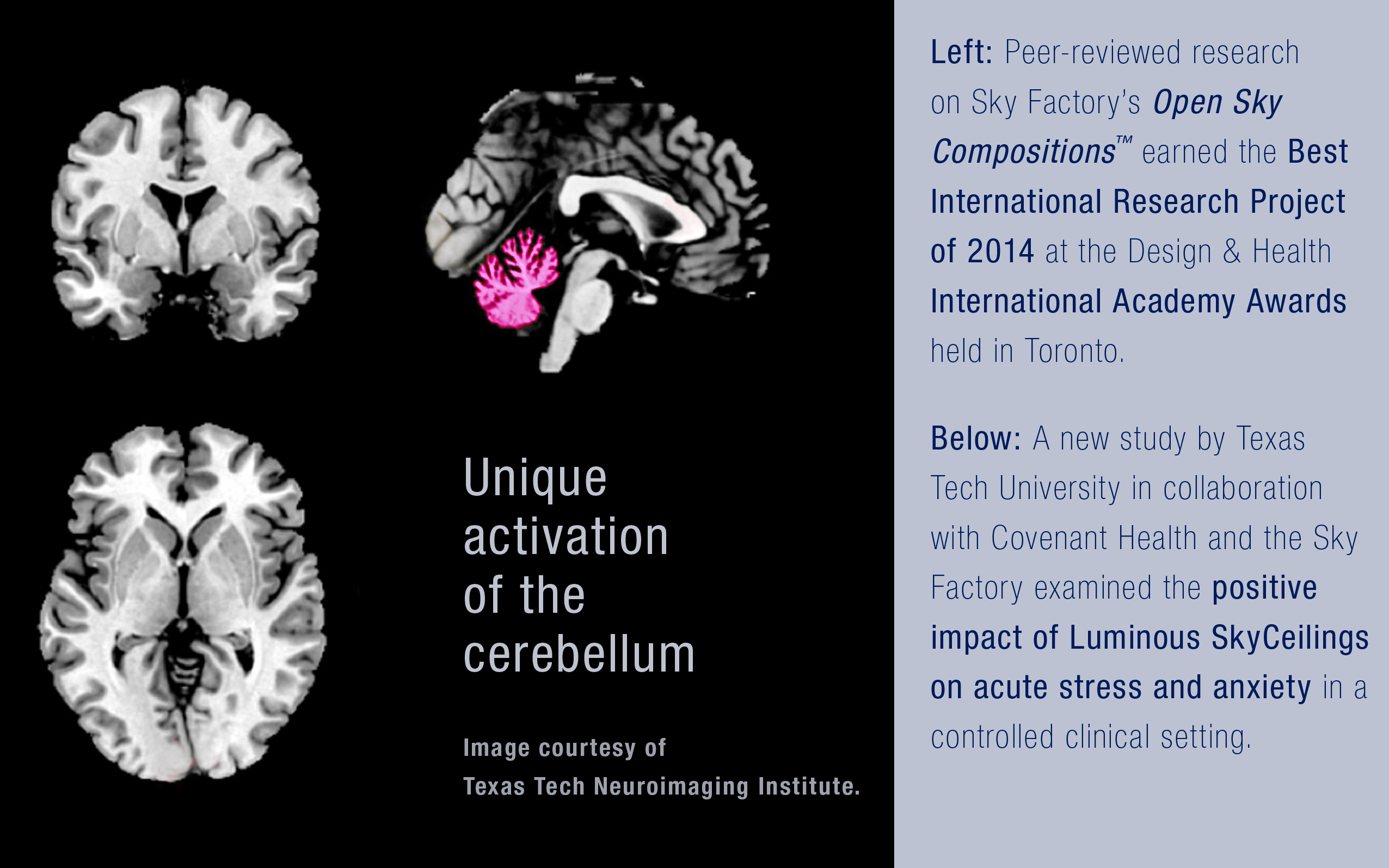

Two studies led by a team of researchers at Texas Tech University’s Department of Design, in collaboration with the College of Human Sciences, were the first to explore whether all nature images impact our organs of perception in the same manner. Taking advantage of fMRI technology, the team designed an exploratory, but highly revealing study.

Unlike representational nature photography, Open Sky Compositions are designed to engage spatial cognition. © 2016 Sky Factory

The team set out to explore brain activation patterns in healthy adults when viewing specifically designed photographic Open Sky Compositions as compared to other types of images, including nature images.

The study was designed to identify areas of the brain uniquely activated by photographic sky compositions specifically designed to evoke a familiar spatial reference frame based on a universal multisensory experience—the experience of looking up at the sky from a secure vantage point under foliage—as compared to other positive, negative, and neutral images.

Prior to this study, there was no conclusive evidence that verified the experience of patients who reported a sensation of expansion when viewing specifically designed sky imagery.

The principal investigator, Dr. Debajyoti Pati, noted that a substantial body of research used behavioral and physiological indicators to measure the positive impact of nature exposure on health and well-being. However, the exact neural mechanism underlying these positive influences had thus far eluded environmental design researchers and practitioners.

The study earned the Design & Health International Academy Award for Best International Research Project in 2014 for indicating that open sky compositions with spatial reference frames engaged areas of the brain involved in spatial cognition (depth perception).

The following year, the same team of researchers published a second paper entitled The Impact of Simulated Nature on Patient Outcomes: A Study of Photographic Sky Compositions in the Health Environments Research & Design Journal. The eight-month study analyzed data from 181 subjects assigned to identical rooms where the only environmental variable was a Luminous SkyCeiling, an illusion of sky, directly above the patient bed.

Dr. Pati noted that “only a handful of studies since Ulrich’s original window study over 30 years ago have set out to measure and quantify the difference a simulated nature intervention can make in a patient room environment.

“We are the first to study and quantify a simulated view to nature designed to be perceived, not as an artifact, but as an architectural feature of the room. Whereas the Neural Correlates of Nature Stimuli study found that Open Sky Compositions, relative to other positive—including nature images, uniquely engaged areas of the brain involved in spatial cognition, this study sought to quantify the benefits in the patient environment,” added Dr. Pati.

These studies have led to a heightened interest in documentation and validation of the therapeutic value of illusions of nature in enclosed interiors. Currently there are studies underway in Canada, the United Kingdom, as well as planned studies at the Qatar Foundation in Doha, Qatar.

What these studies uncover will undoubtedly be applicable to a myriad of other commercial environments where we face the same set of deleterious variables: enclosed interiors and captive populations.

In a rapidly urbanized world where countless trading floors and call centers, classrooms and laboratories, fitness centers and child care facilities, retail boutiques and department stores, all share the same environmental design constraint—isolated interiors—it is imperative that architects and designers understand the genuine restorative value of illusions of nature to alter the observer’s experience for meaningful wellness and productivity gains.