Known for his high risk efforts in advancing an eco-friendly mission for decades, Denis Hayes, president of the Bullitt Foundation, has fueled the ever-growing environmental movement in America since he organized the first Earth Day in conjunction with then-Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson in 1970.

Thanks to his efforts as a leader on environmental issues, sustainable strides in this country have been taken on multiple fronts. And Hayes’ most recent bet on creating the first significant net positive energy office building paid off. On April 1, 2015 the Bullitt Center became the first office building to earn Living Building certification.

The 52,000 square-foot, six story Bullitt Center stands as a shining example of the accomplishments Hayes and the Foundation have achieved in their quest to remain at the forefront of the sustainability movement. Photograph ©Nic Lehoux

The Bullitt Center

Hayes opted to develop the building after searching to no avail in Seattle for environmentally sensitive office space that would meet his criteria. “We were looking for offices that reflected our values,” says Hayes, adding that “our focus is on human ecology with an emphasis on how we can design built environments that are proper, healthy habitats for our species.” Once the head of the Solar Energy Research Institute during the Carter Administration, Hayes continues to advance environmental initiatives supported by the Bullitt Foundation, which offers grants to organizations working on environmental projects in the Pacific Northwest. The 52,000 square-foot, six story Bullitt Center, which is owned by the Bullitt Foundation, stands as a shining example of the accomplishments he and the Foundation have achieved in their quest to remain at the forefront of the sustainability movement.

The Living Building Challenge

The structure was designed to achieve certification as a Living Building, which is significantly more ambitious than LEED Platinum certification. To meet it, a building must generate as much energy as it uses each year and use rainwater for all purposes, including drinking. It must also meet lofty standards for eco-friendly materials and indoor air quality.

Located on a site that was a forest filled with Douglas fir trees before European settlement, the building was designed by the Seattle-based Miller Hull Partnership to function as a tree would. “Not only does it provide shelter and sustenance for its users, like a tree would for deer, elk, birds, and squirrels, it also produces its own energy from the sun and rain, it doesn’t produce toxins, and it recycles its waste as nutrients.”

The Bullitt Center was designed by the Seattle-based Miller Hull Partnership to function as a tree would. Photograph ©Nic Lehoux

A building for all

Since the Bullitt Foundation operates with only seven employees and needed just 4,000 square feet for its own business, the building was designed to be leased out to additional tenants to make it commercially viable.

Among the numerous companies and organizations that have opted to occupy the building are the International Living Future Institute, founder of the Living Building Challenge, which defines the standards for Living Building certification, various small companies, and a substantial engineering firm, which completely tailored its business processes to drive down its energy demand by 82 percent with no loss in productivity or convenience. “We tell our tenants how many kilowatt hours of energy they’re allowed to use, and if they exceed it they pay a stiff penalty for high energy bills,” says Hayes.

The Seattle office of the International Living Future Institute, founder of the Living Building Challenge, calls the Bullitt Center home. Photograph ©Benjamin Benschneider

Harnessing solar energy

The building relies on solar energy to meet its electricity needs, so educating tenants on ways to reduce consumption is necessary to keep the building’s energy use in check. Yet, since the building began operating about two years ago, its energy generating and energy conservation systems not only allow it to meet all of the energy needs of the Bullitt Foundation and other tenants in the building, but also enable it to produce more energy than it consumes, making it the first commercial office building of its size in the U.S. to operate as a net positive energy structure, generating 60 percent more energy than it used in 2014.

“The Energy Use Index (EUI) for an average office in Seattle is 95, under our new energy code the index will fall to the low 50s, for LEED Platinum buildings it reaches the low 30s, and for our building we aimed for 16,” says Hayes. “But it has exceeded our wildest hopes. Our EUI in 2014 was 9.4, making it by far the most efficient office building in America.” Its excess power is sold back into the electrical grid for use by others.

Creating an eco-friendly space

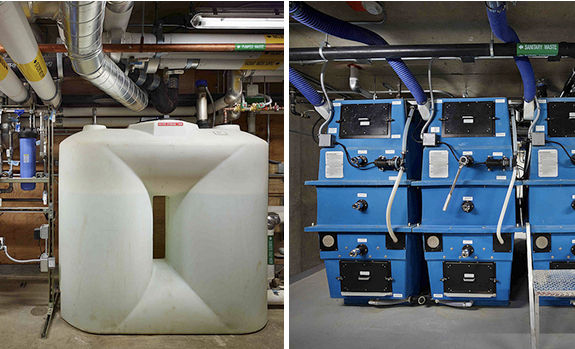

A few of the building’s other eco-friendly highlights include a robust rainwater collection and filtering system, onsite treatment of sewage, composting toilets, and project certification from the Forest Stewardship Council—the first office in the U.S. to achieve this status.

Red-List Materials

The building also excludes 362 “Red List” elements that are toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, or endocrine disrupting. Materials and furnishings devoid of “Red List” elements were also chosen by Robin Chell, principal of Seattle-based RCD, who worked with the Bullitt Foundation to design the interiors of its own offices. “Because we needed to avoid products that contained elements on the “Red List,” everything was rigorously scrutinized and had to be formaldehyde free,” explains Chell.

A few of the building’s eco-friendly highlights include a robust rainwater collection and filtering system, onsite treatment of sewage and composting toilets. Photograph ©Benjamin Benschneider

Acoustic Performance

The Bullitt Foundation also needed soft furnishings that would serve as acoustical buffers in the space. So, in keeping with the notion of biomimicry, which guided the design of the building’s mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and lighting systems, Chell chose felt art works, wool-upholstered soft furnishings, and earth- and moss-inspired eco-friendly modular carpet from Interface’s Urban Retreat collection.

“We wanted to bring in colors of nature with finishes, art, and furnishings that were inviting, stimulating, and reflected their ethos,” Chell explains. “So we started with the carpet, which inspired the tones of the other elements. Aside from offering environmentally friendly products, Interface has an amazing array of design innovations that are almost always ahead of the curve,” Chell adds. Honored with IIDA’s People’s Choice award last year, Chell’s design is ultimately as eco-friendly as it is practical and appealing to the eye.

In keeping with the notion of biomimicry, Robin Chell Design chose earth- and moss-inspired eco-friendly modular carpet from Interface’s Urban Retreat collection for the space occupied by the Foundation. Photograph ©Brent Smith Photography

“We wanted to bring in colors of nature with finishes, art, and furnishings that were inviting, stimulating, and reflected their ethos,” Robin Chell explains. Photograph ©Brent Smith Photography

Tackling project challenges

Since Seattle’s climate is often cloudy and gray, creating a six story building that relies on solar energy to meet its power needs was risky. But Hayes was convinced that the potential return on the investment made taking the chance worthwhile. “Other buildings have been designed to meet these sustainable standards, but they are small—usually 2,000-6,000 square feet,” he says. “We wanted to dramatically increase the scale and felt it was doable. Even if we set out and failed, we thought it was still a heroic leap, so we decided why not aim for the moon and give it a shot? We wanted to be taken seriously not only by the academic community, but also by those who actually build.”

Judging by the number of tours (about six per week) that the Bullitt Center hosts in its building for developers, architects, and facility managers, Hayes appears to have succeeded in capturing their attention. And if the building achieves Living Building certification, which it hopes to do later this year, the building will no doubt generate even more interest.